Explore the Watershed

What is a Watershed?

Pennsylvania has more rivers, streams, and creeks than almost any other state—over 86,000 miles of flowing water, second only to Alaska. No matter where you live or travel within the state, you are always within a watershed. A watershed is an area of land where all the rain, melting snow, and groundwater flow toward the same low point, usually a creek, stream, or river. The shape of the land—its hills, valleys, and slopes—determines how the water moves. Smaller watersheds feed into larger ones, and together they form major river basins that ultimately carry water to the ocean.

The Neshaminy Watershed

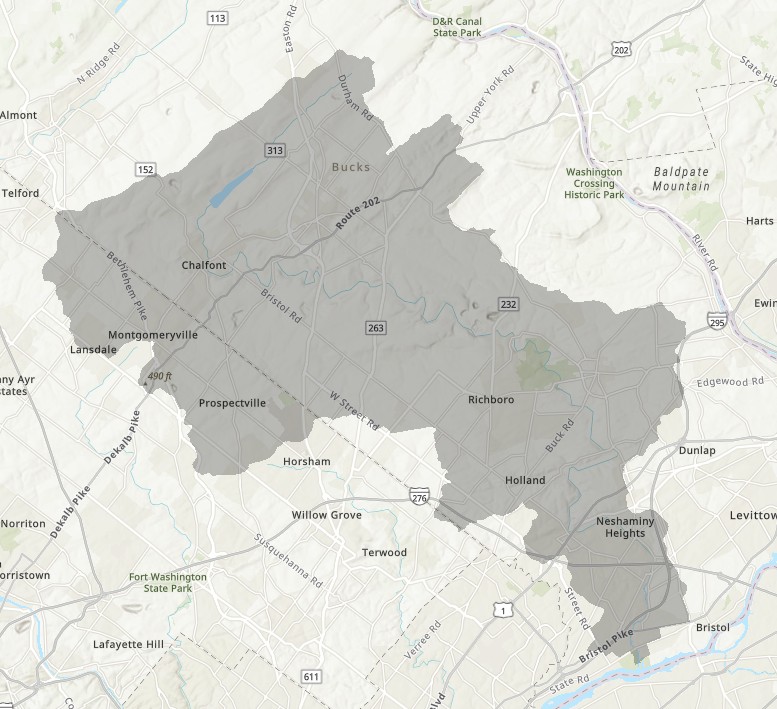

The Neshaminy watershed spans a large portion of Bucks County and a smaller section of Montgomery County. Its main waterway is the Neshaminy Creek, a 40.7-mile stream that winds through Bucks County. The watershed also includes the Little Neshaminy Creek—its major tributary—along with Newtown Creek, Cooks Run, and three separate tributaries all known as Mill Creek. Altogether, the watershed covers roughly 236 square miles.

Map of the Neshaminy Watershed

Headwater Streams

Two important headwater streams form the upper part of the watershed: the West Branch and the North Branch of the Neshaminy Creek. The West Branch is officially documented as beginning at an unnamed pond near the Bucks–Montgomery county line. Local utility staff have also identified a small, spring-fed flow emerging from beneath Lansdale that contributes to its upper reaches. The North Branch begins in Plumstead Township, Bucks County, with its headwaters located east of PA Route 413 (Durham Road) and north of the village of Gardenville. As it flows south, the North Branch is dammed to create Lake Galena, an important recreational and ecological resource in Peace Valley Park.

These two branches flow south and join at Twin Streams Park in Chalfont, forming the main stem of the Neshaminy Creek.

The Neshaminy watershed is part of the larger Delaware River Basin. As the creek flows southeast through Bucks County, it passes through parks such as Tyler State Park before reaching the Delaware River at Neshaminy State Park in Bensalem.

The name "Neshaminy" comes from the Lenape people and is commonly interpreted as "the place where we drink twice."

History and Cultural Heritage

The Neshaminy Watershed has a long human history shaped first by the Lenape people, who relied on its springs, forests, and fertile valleys for travel, settlement, and fishing. Many place names still reflect their influence, including "Neshaminy," derived from a Lenape term referencing nearby streams. As European settlers moved into the region in the 1700s, the watershed became a center of farming, milling, and early industry. Dozens of grist mills, bridges, and small villages grew along the creek's banks, using its water as a power source and transportation corridor. Over the centuries, the watershed also experienced major floods, land-use changes, the construction of dams such as the one that created Lake Galena, and the expansion of towns from Montgomery County through Bucks County. Together, these layers of history form a cultural landscape that continues to shape how communities relate to the creek today.

Ecology and Wildlife

The watershed supports a diverse mix of habitats, from forested headwaters and wetlands to meandering lowland streams and riparian corridors. These ecosystems provide food, shelter, and migration pathways for many species of fish, birds, amphibians, and mammals. Native plants stabilize streambanks, filter runoff, and create shade that keeps water temperatures suitable for aquatic life. In some areas, wetlands host herons, turtles, and amphibians, while upland forests support deer, foxes, owls, and seasonal bird migrations. The health of this natural community depends heavily on water quality, stormwater management, and the protection of intact habitat. Even small conservation actions—such as restoring native buffers or removing invasive species—can make a meaningful difference in supporting biodiversity throughout the watershed.

Water Quality and Environmental Challenges

The Neshaminy watershed continues to experience significant water-quality pressures, many of which stem from decades of suburban growth and changing land-use patterns. As farmland and open space have been converted into residential neighborhoods, commercial corridors, and road networks, the amount of impervious surface has steadily increased. These hard surfaces prevent rainwater from soaking into the ground and instead funnel large volumes of stormwater directly into creeks. This accelerated runoff carries sediment, nutrients, oils, road salt, lawn chemicals, and other pollutants into local streams, while also causing rapid swings in water flow that erode streambanks, degrade habitat, and stress aquatic life.

Overall Water Quality

Stormwater runoff, sedimentation, road-salt contamination, and wastewater discharges remain the major drivers of impairment within the watershed. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection identifies sediment impairment across many stream reaches, with formal requirements for sediment-load reductions to improve ecological conditions. Monitoring has also revealed elevated chloride levels — particularly in smaller tributaries and near developed areas — a clear sign of excess winter road-salt use. In some localized areas, nitrate concentrations rise during certain seasons, reflecting both lawn-fertilizer application and legacy wastewater influences.

Effects of Development and Land-Use Change

Long-term development has reshaped the watershed's hydrology and water chemistry. As impervious cover expands, rainwater that once infiltrated into soils now moves quickly over pavement and rooftops, picking up pollutants and delivering them into the creek with little natural filtration. This has contributed to warmer water temperatures, greater turbidity, and more frequent "flashy" flow conditions where streams rise and fall rapidly after storms. Over time, these conditions reduce habitat complexity — scouring out pools, burying gravel beds, and destabilizing banks — which limits the ability of fish, aquatic insects, and amphibians to thrive.

Ecological Indicators

Biological assessments consistently show limited populations of sensitive aquatic species, an indicator that portions of the creek do not meet state criteria for fully supporting aquatic life. Species that require clean, cool, stable environments have become scarce, replaced by pollution-tolerant organisms better adapted to storm-driven disturbances. These patterns confirm that watershed health is closely tied to land-use decisions, stormwater management, and the cumulative impact of development over time.